(This publish initially appeared as a visitor publish on Linda Bennett Pennell’s weblog, History Imagined.)

In researching my historic novels set in nineteenth-century America, I’ve come throughout quite a few individuals, now obscure, who need to be remembered for his or her heroism. One is David Ruggles, a black abolitionist.

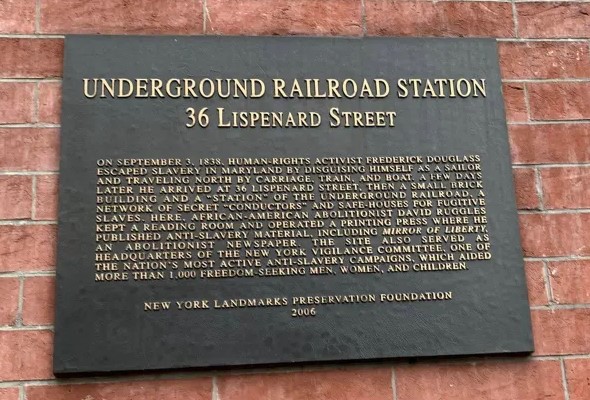

Born in Lyme, Connecticut, on March 15, 1810, Ruggles, the son of a blacksmith, took to the ocean at age fifteen and ended up in New York Metropolis, the place he grew to become energetic within the abolitionist motion and ran a grocery retailer for a time frame. In 1834, he moved to Lispenard Avenue in decrease Manhattan and opened a bookstore and circulating library specializing in abolitionist literature. Quickly he started publishing his personal pamphlets—a daring transfer in a metropolis that was not notably pleasant to the anti-slavery motion. His retailer was set on fireplace in 1835. Unintimidated, Ruggles helped kind the New York Committee of Vigilance, which helped escaped slaves and fought in opposition to the kidnapping of each free blacks and escapees. His home would quickly turn into a cease on the Underground Railroad.

In 1838, Frederick Bailey, a fugitive from slavery, was directed to Ruggles’ home and spent no less than every week there. Whereas there, Bailey summoned his fiancée from Baltimore to New York, and the couple married in Ruggles’ home. (Ruggles himself was a lifelong bachelor.) On Ruggles’ recommendation, Bailey modified his surname to Johnson, however quickly would change it once more, changing into generally known as Frederick Douglass. Douglass was one in all a whole bunch whom Bailey helped to freedom.

Sadly, Ruggles’ eyesight started to deteriorate when he was nonetheless a younger man, making it untenable for him to proceed his publishing actions, which included a journal, the Mirror of Liberty. Associates invited him to remain on the Northampton Affiliation of Schooling and Trade, a cooperative neighborhood simply outdoors of Northampton, Massachusetts. He arrived there in 1842, however his normal well being was failing as effectively. Ruggles lastly tried hydrotherapy, generally known as the “water treatment,” below the supervision of Dr. Robert Wesselhoeft, who operated a well-liked water-cure in Brattleboro, Vermont, however suggested Ruggles by letter. As Ruggles’ biographer, Graham Russell Gao Hodges, factors out, Dr. Wesselhoeft was apparently unwilling to threat the social outrage that might consequence from having Ruggles bathing facet by facet with white shoppers.

Regardless of the remedies, Ruggles’ well being and eyesight improved solely marginally, however he was happy sufficient with the outcomes to start treating sufferers himself. Amongst his sufferers was a reluctant Sojourner Fact, who grumbled, “I shall die if I proceed in it, and I could as effectively die out of the water as in it.” After ten weeks, nonetheless, she admitted that she “had by no means loved higher well being in her life.”

Ruggles quickly opened his personal water-cure institution within the Northampton space. One other of his sufferers was abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who stayed there through the summer season of 1848. Writing to Maria W. Chapman on July 19, 1848, Garrison said: “The expertise of the primary day runs thus: — a half tub (which I ought to take into account a complete one and 1 / 4) at 5 o’ clock, A.M.; rubbed down with a moist sheet thrown over the physique at 11 o’clock; a sitz tub at 4, P.M.; a foot-bath at half previous 8, P.M.; and at 5 this morning, a shallow tub which is to be adopted at 11 by a twig baptism.” In a letter to his spouse on July 23, 1848, Garrison bragged that he had withstood the pains of being “packed in a moist sheet, or drenched from head to foot, or immersed throughout” and had not “uttered a groan, or heaved a sigh, or shed a tear, or faltered for a second.” He famous that there have been 19 sufferers, largely males, and added, “There doesn’t appear to be any pro-slavery among the many sufferers; if there actually is, it has not been manifested by any phrase or signal, and I hope it will likely be washed out of them.” Upon his discharge, Garrison proclaimed, “My aversion to chilly water has been pretty conquered. I’m now its earnest advocate.” Different sufferers of Ruggles included Mary Brown, whose husband John would later be hanged for main the raid on Harpers Ferry. Mary, who had had quite a few kids and had been ailing for a while, informed her son-in-law that she believed that the water treatment can be “her solely salvation.” Later, she would use the water-cure to deal with her family’s illnesses.

Sadly, Ruggles couldn’t treatment himself. Though he ran his water treatment virtually till the top, he died on December 16, 1849. He was not but forty. Ruggles was buried in his household plot in Norwich, Connecticut. Many would pay tribute to this man who had led a brief, however full and heroic life. Frederick Douglass later recalled him as that “whole-souled man, totally imbued with a love of his bothered and hunted individuals.”

Sources:

Frederick Douglass, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855).

Graham Russell Gao Hodges, David Ruggles: A Radical Black Abolitionist and the Underground Railroad in New York Metropolis (Chapel Hill, NC: College of North Carolina Press, 2010).

The Liberator, July 27, 1849 (commercial)

Walter M. Merrill, ed., No Union With Slave-Holders: The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison, 1841-1849 (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard College Press, 1973).

Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz, The Tie That Certain Us: The Girls of John Brown’s Household and The Legacy of Radical Abolitionism (Ithaca and London: Cornell College Press, 2013).

Joel Shew, The Hydropathic Household Doctor (New York: Fowler and Wells, 1854).

Margaret Washington, Sojourner Fact’s America (Urbana and Chicago: College of Illinois Press, 2009).