by Nathália Susin Streher

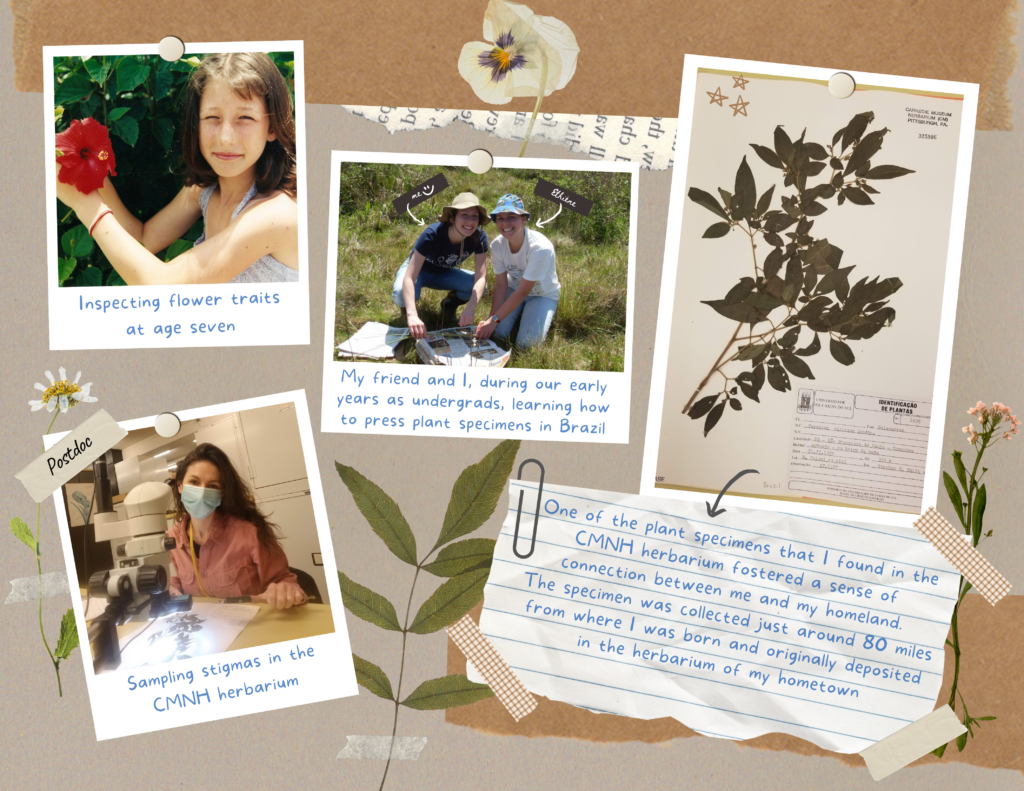

Do you ever surprise what made you pursue your desires in life? After I ask myself this query, it inevitably takes me again to my childhood and the indelible reminiscences that rising up in probably the most biodiverse nation on this planet left on me. From the variety of fruit bushes and the tiny animals that crawled them in my yard to the numerous ecosystems within the surrounding areas, residing in Brazil has formed my notion of nature and sparked a singular curiosity in regards to the number of types and interactions I may observe. Because the little scientist in me grew up, fueled by the fascination with the gorgeous mysteries of flowers, it naturally guided me towards the trail of learning crops and their interactions.

As I stepped into the world of science, my first paid alternative as an undergrad in biology was in a small herbarium. There I discovered about preserving plant specimens collected from nature and their significance for identification and classification of plant species. What I didn’t notice again then was that herbaria retailer extra than simply names and relations amongst species; additionally they present a way to research ecological interactions like those that captivated me as a baby. I stored that flame of curiosity from my childhood alive and got here to the US as a postdoc researcher. My analysis group on the College of Pittsburgh and I’ve been incorporating some unconventional makes use of of herbarium materials into our analysis. In a recent scientific publication, we used herbarium specimens (many sourced from the CMNH herbarium) to discover an important ecological mutualism between animals that go to flowers for meals and crops that require go-betweens to move their pollen—a course of referred to as pollination.

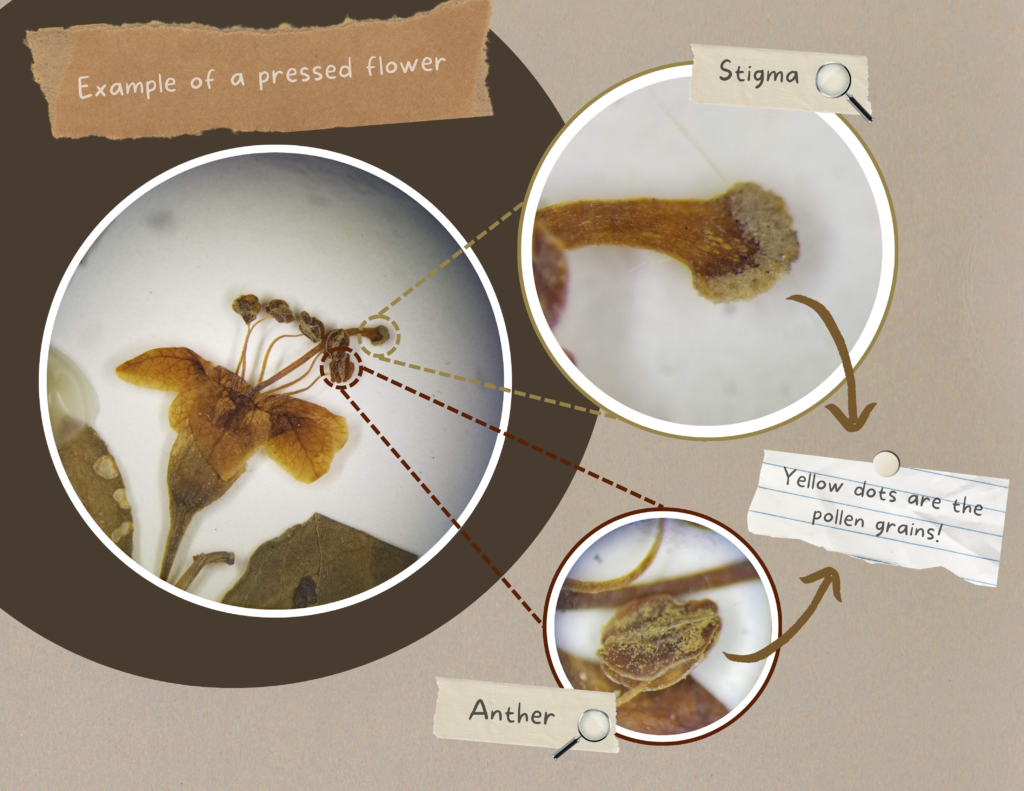

In pollination biology, it’s common to research floral traits as a result of they play an important position in mediating plant interactions with their pollinators. For instance, crops with lengthy floral tubes are sometimes pollinated by morphologically matching long-tongued pollinators. Whereas sure floral traits, akin to seen coloration and scent, could also be altered or fully misplaced through the drying strategy of plant specimens, most of the different traits stay accessible even after years of preservation. Thus, so long as the herbarium sheet incorporates not less than one flower, worthwhile organic data may be extracted to grasp plant-pollinator interactions.

On this research, we used herbarium specimens to disclose the community of previous plant-pollinator relationships. Particularly, we sampled a small piece of the flower, the stigma, which is the construction that receives pollen grains delivered by pollinators. As pollinators might go to a number of plant species flowering collectively, inspecting stigmas can unveil a plant’s pollination story. By assessing the variety of pollen grains morphologically distinct from the goal species, we acquire insights into whether or not the goal species interacted with many or only some different plant species by means of pollinator sharing.

Leveraging herbarium specimens for ecological questions gives a singular benefit, as they supply historic, spatial, and long-term views to scientific research—dimensions that will in any other case be difficult to achieve. In research of plant-pollinator interactions, researchers usually depend on direct pollinator commentary information, which, whereas splendid, has limitations akin to being time-consuming, pricey, and depending on varied situations. Pollen deposited on stigmas of herbarium specimens arises as a worthwhile various when direct pollinator commentary is unfeasible. Herbaria provide scientists a handy strategy to examine quite a few plant species from all over the world. Actively incorporating these specimens into analysis not solely retains the collections dynamic but in addition magnifies their total significance. Very like the plant-pollinator interplay—it’s a win-win situation. I hope our work evokes others to understand herbarium collections as guardians of biodiversity and encourages scientists to unlock the hidden potential of their valuable specimens.

Past the scientific pleasure of unraveling the pollination story inside herbarium specimens, I as soon as once more appeared to have missed yet one more potential interplay they might reveal. Whereas going by means of the cupboards housing the specimens at CMNH, I unexpectedly encountered crops collected from the identical area the place I used to be born and raised in Brazil. I by no means thought that an previous, dried plant may make me really feel nearer to my homeland. Residing overseas to pursue the scientific dream is not any straightforward feat—totally different language, totally different tradition. However that second was a reminder of my childhood reference to nature that introduced me right here. Now, I see herbaria not solely as guardians of biodiversity but in addition as promoters of a way of belonging in us.

Nathália Susin Streher is a postdoctoral analysis affiliate within the Ashman Lab of College of Pittsburgh.

Associated Content material

Collected On This Day in 1950: Dutchman’s Breeches

What Do Botanists Do On Saturday?

Collected On This Day in 1944: Squarrose Goldenrod

Carnegie Museum of Pure Historical past Weblog Quotation Data

Weblog writer:

Streher, Nathália Susin

Publication date:

Might 8, 2024

Share this submit!